How One TV Station Covers Disruptive Weather

By Tim Heller

Talent Coach and Weather Content Consultant

Broadcast meteorologists naturally do their best work when the weather is bad. When severe thunderstorms, tornados, hurricanes and flash floods threaten the local area, you can usually count on your TV weather team to be on-air. These high-impact moments are what meteorologists study, train and prepare for their entire careers.

The National Weather Service (NWS) defines a "severe thunderstorm" as one that produces "a tornado, winds of at least 58 mph and/or hail at least 1 inch in diameter." These storms are considered strong enough to cause structural damage and will prompt the NWS to issue a severe thunderstorm or tornado warning.

These warnings trigger a chain reaction at local TV stations. The severe weather alert will usually "crawl" across the bottom of the TV screen. The weather team might produce a live weather update. Push alerts will be sent out on the station-sponsored app. Warning maps will be published on social media accounts. And more.

What about those times when the storms aren't severe, as defined above?

"Time and time again, research into the importance of weather shows that it's not only the severe weather that matters to viewers,” said Bernice Kearney, News Director at KSAT 12 in San Antonio. "In fact, it's the weather events that get in the way of the life we intend to live. Viewers aren't meteorologists. If the weather disrupts their plans, that's the weather they're most interested in."

Pea size hail might not be big enough to cause damage, but it's alarming when there's enough to cover the ground. Winds 35 to 45 mph are strong enough to knock down weaker tree branches. Torrential rain can stop traffic. One flash of lightning is enough to pause outdoor events and send people running for cover. While not considered "severe," these storms are still disruptive.

Local TV stations have an opportunity to establish themselves as the go-to weather expert in their community by delivering essential information when the weather matters. Viewers don't care if the National Weather Service considers a storm to be "severe." They care about the storm rumbling through their neighborhood. Smaller, short-lived weather events are just as important to the people affected.

Live weather updates in the palm of your hand

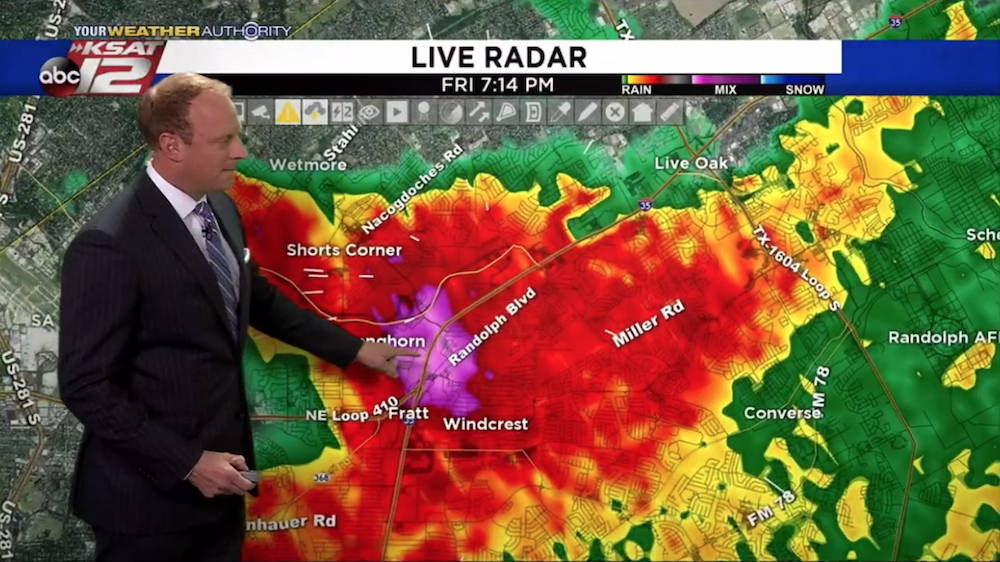

Adam Caskey gets it. He's the evening meteorologist at KSAT 12. Almost every time storms threaten some part of central Texas, Caskey fires up the studio lights, gathers the production crew and produces a live "appcast" on the weather app developed by KSAT's corporate owner, Graham Media Group.

"What's the first thing today's viewers do when the sky gets dark? Check their phone,” Caskey said. “They want to know what's happening and when it's all going to change. The appcast provides live answers to many of their questions. We broadcast live from our studio and chroma key directly to the palm of their hand."

Some appcasts are 15 to 20 minutes long, while others might last an hour or two, depending on the weather, of course. These live updates are casual and personal. Caskey references specific cross-streets and neighborhood landmarks. He'll sometimes pause to update TV viewers, giving those watching the appcast a behind-the-scenes view. And he often includes the rest of the weather team, who might be monitoring NWS Chat, gathering photos sent in from viewers or driving toward the storm in the station's Stormtracker vehicle. All this for storms that aren't, by definition, severe.

"Acknowledging the role of disruptive weather in our viewing area, and not diminishing how important it is to the day-to-day lives of our neighbors, is one of the ways our meteorologists can continue to build loyalty and trust among our viewers," Kearney said.

There's no hype here. You get the sense that Caskey and the rest of the weather team genuinely care about the comfort and safety of their viewers. They take time to thoroughly analyze the weather and share their observations. They realize a moderate downpour can be inconvenient if it falls in the wrong place at the wrong time.

"For non-severe weather, I still focus heavily on radar," Caskey said. "I also incorporate elements from the newscast and run through the forecast as well. I take my time and repeat the process several times because we've found that people tune in at various moments. Also, if the storms aren't affecting a certain area when the push alert goes out but are moving that way, we know those folks will tune in when the storms arrive."

People seem to appreciate the extra effort. Caskey said more than 100,000 people watched the appcast during one recent storm. He has heard from San Antonians on vacation who tune in to see how the storms affected their neighborhood. Plus, he added, "We're all familiar with how people in the outskirts of the viewing area often feel neglected. This is an opportunity to include them and focus on them without time restraints. It's also the best way to broadcast to people who have lost power and internet."

The weather where you live

To paraphrase a well-known saying, "All weather is local." Whether or not a storm is "severe" is a technicality. It doesn't matter to everyday people. What matters is how the weather is affecting their neighborhood.

Small storms can have a big impact. People might not need to seek safe shelter. However, disruptive weather events still could cause people to alter their plans, run indoors or pull over to the side of the road until the weather clears. Furthermore, how will viewers know storms aren't strong enough to produce damage if broadcast meteorologists don't tell them?

Local TV station weather teams usually do an excellent job connecting with viewers during severe weather. But we can't build a loyal following if we only show up when warnings are issued. We need to deliver essential information every day, on every platform. Not just when the weather is severe and not just on TV.

Tim Heller is an AMS Certified Broadcast Meteorologist, Talent Coach, and Weather Content Consultant. He helps local TV stations and broadcast meteorologists communicate more effectively on-air, online, and on social media.