What I learned in Russia about the dangers facing U.S. newsrooms today

Dan Shelley

RTDNA President and CEO

In June 2017, just a few months after joining the RTDNA staff, I was asked to spend a week in Russia as part of a cultural exchange program that was started by President Eisenhower and Chairman Khrushchev in the 1950s. My mission was to talk about the advantages and potential dangers of social media, including its ability to quickly spread disinformation and misinformation.

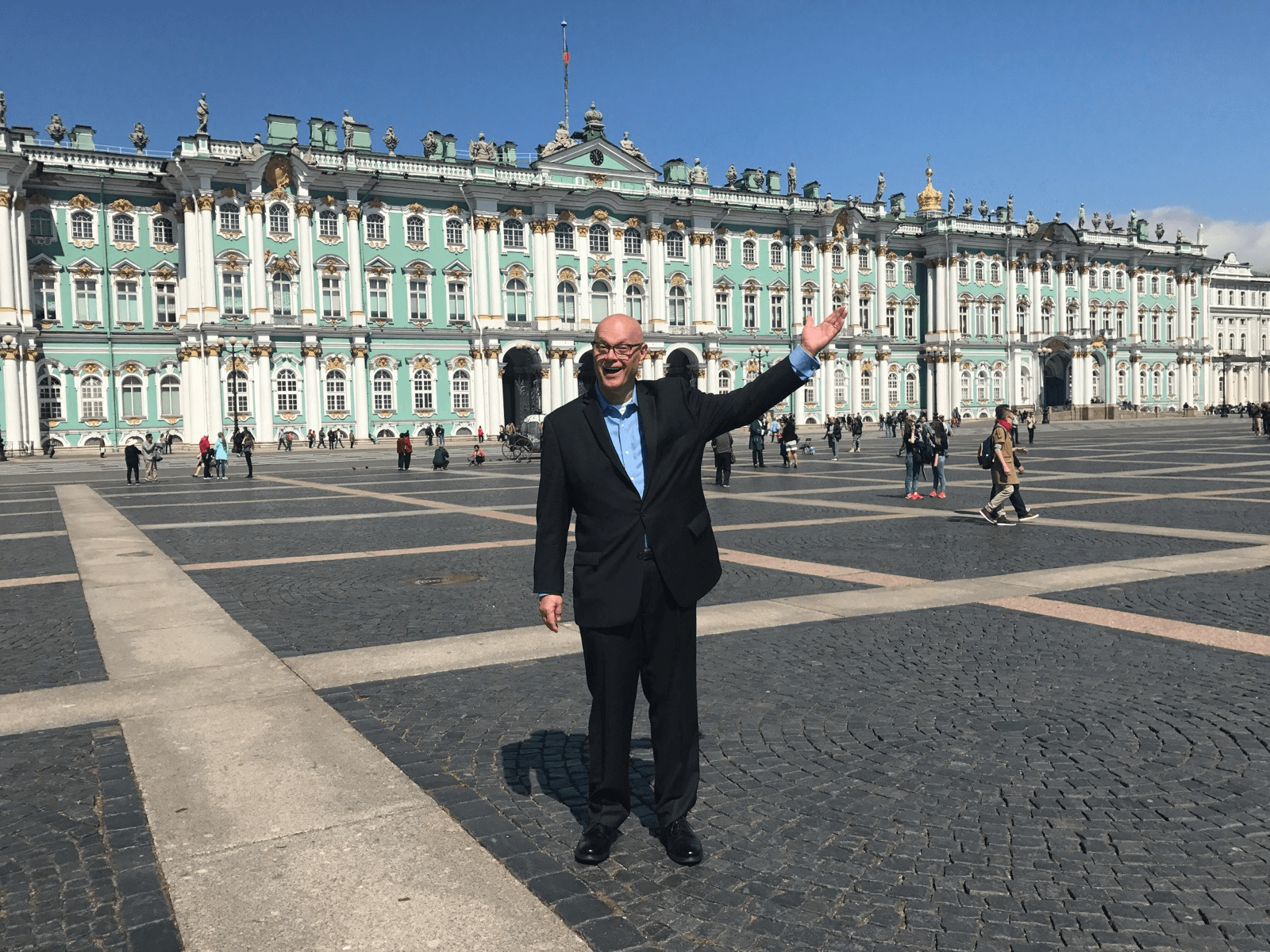

I first visited St. Petersburg, where I, through an interpreter, spoke to members of the local press club. I had already been briefed that, at that time, at least 80 percent of the Russian news media was government-controlled. Only about 20 percent consisted of independent journalists. Even so, if you were an independent Russian television or radio journalist, your station’s transmitter was owned by the government. They could flip a switch and take you off the air if you broadcast anything the Kremlin or local government officials didn’t like.

After my presentation, it was time for Q&A. A gruff-looking middle-aged man stood up, placed an audio recorder on the podium in front of me, and asked, “What do you have to say to President Putin about his horrible treatment of journalists, including the murders of journalists during his time in power?”

OK, this guy was obviously an independent journalist. His question sent my mind into overdrive. Sure, I’d like the chance to confront Putin, but not by saying something that could possibly get me thrown into a Russian prison. After a few seconds that seemed like hours, an answer finally came to me.

“RTDNA condemns mistreatment and violence against journalists anywhere in the world,” I replied, a little proud of myself for giving what I thought was a strong but benign answer to a purposefully incendiary question. The journalist snatched his recorder off the podium and stomped back to his seat, obviously dissatisfied with what I had said.

Then a young woman reporter stood up and, reading from her iPhone, asked her question: “How do you explain the US media’s refusal to report on NATO’s encroachment into sovereign Russian territory by conducting military exercises in the Baltic States?”

Obviously, she worked for a state-run news outlet.

Ignoring the premise of her question, I answered that the US news media had always reported extensively on important NATO activities. She didn’t like that answer, either. The rest of my press club appearance was unremarkable.

While in St. Petersburg, I also spoke to students at a communications college, where the students, and especially the faculty, treated me like a rock star. Or a geek in a circus sideshow. It was sometimes hard to tell. Nevertheless, afterward, the headmistress insisted on taking me to lunch in a very fancy restaurant where she ordered for me. Cold borscht, served with a bib to protect my suit and shirt from any of the beet-based soup I may have spilled. For the record, I didn’t. And the borscht was amazingly good!

After lunch, I was taken by car to a nondescript apartment building well outside the city center, where I met with the editors of an independent news website that reported mostly on local issues, but also, occasionally, on national and international affairs. After walking up three flights of stairs and down a quiet hallway, I was shown into an apartment. I was asked to remove my shoes so that the downstairs neighbors couldn’t hear my footsteps.

Inside were at least a dozen busy journalists – all in stocking feet – working hard on their computers. I spent about an hour visiting with the editors and learning the intricacies and dangers of presenting the public with no-holds-barred factual journalism, of how they were able to speak truth to power, but always with eyes in the backs of their heads. It was perilous but critical work, and I left the apartment extremely proud of those intrepid truth-seekers.

The next day I went to Moscow. But during the nearly four-hour train ride, I couldn’t stop thinking about the independent audio reporter who confronted me about Putin’s bullying of journalists, and especially about the courage and determination of the independent digital journalists who accomplished so much despite the risks. Now, of course, post-Ukraine invasion and its accompanying anti-press freedom laws in Russia, I wonder what happened to them all. And I worry.

In the capital city, I was scheduled to give an evening presentation to members of the public at the Russian State Library. So, to kill time during the day, my interpreter and I made the obligatory tourist visit to Red Square, where I had my picture taken in front of the iconic St. Basil’s Cathedral just outside the Kremlin walls. We couldn’t visit Lenin’s tomb, the other must-see site there, because it was closed for renovations.

When we returned to my hotel late in the afternoon, my interpreter got an email from the library saying that my presentation had to be moved to another venue because of a “maintenance issue.” I use quotation marks because neither she nor I believed that was the real reason. Instead, she was told, the library had arranged for me to give the presentation at a coffee shop, and an address was provided. Not the name of the coffee shop, just the address.

A couple of hours later, we got into a taxi and gave the driver the address. He had no idea where it was. After consulting with someone on the phone, he started driving. And driving. And driving. To the outskirts of the city center, into a neighborhood of shops and restaurants. All of the streets were torn up for construction. He found the address, and it was some kind of store. After looking around for several minutes, we realized that the coffee shop was on the second floor of the store, accessible only by one flight of outdoor rickety wooden stairs.

When we went inside, we discovered the proprietor had no idea we were coming. After my interpreter explained what I was up to, he told us I could make my remarks in the back, in an area furnished with old overstuffed sofas and chairs.

I didn’t expect anyone to show up, given how difficult the library had made the situation. But to my surprise, about 10 people came. They were all in their late teens or early 20s. They listened with interest and then, when I invited their questions, not one person asked about my presentation. Instead, they wanted to confront an American about evidence that Russia had interfered in the 2016 presidential election. We were still in the initial six months of the first Trump administration, after all.

I particularly remember one young man’s question, partly because he spoke perfect English and partly because he was quite indignant. “How dare you accuse Russia of interfering with your election when, during the Cold War, the US routinely interfered with elections in the Soviet republics?” The irony was not lost on me, and I told him so, emphasizing that it was my personal view and not that of RTDNA or the cultural exchange program that had paid for my trip.

The next day, I returned home to New York via Frankfurt, and the only issue I had was a US immigration officer at JFK airport who got angry with me when I told him I was returning from Russia. He carefully examined my passport and Russian visa, and spent several minutes perusing something on his computer, but eventually let me through.

I recount all of this because it sometimes seems as though the Russia I visited in 2017 is not dissimilar to certain things that are happening now in the United States, specifically as it relates to press freedom.

To be clear, I am not engaged here in an overarching critique of the Trump administration or its general ideologies and policies. But I am most certainly critical of the current US government’s brutal assault on the American public’s ability to receive factual news and information.

Lawsuits against news organizations for editing political interviews, for misstating the president’s degree of liability in a civil sexual assault lawsuit, and for reporting on a birthday message Mr. Trump allegedly sent to Jeffrey Epstein more than two decades ago. Denying access to a wire service for referring to the Gulf of Mexico as the “Gulf of America,” but not quite the way the president prefers. A Trump-appointed FCC chairman is opening and reopening investigations into broadcast licensees because of the content of their news reporting.

Perhaps even more egregiously, an administration and a Congress that just rescinded public funding initially approved just months ago for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, effective in October. NPR and PBS will continue to operate, although slightly hamstrung by losing their portions of federal revenue. But dozens of local NPR- and PBS-affiliated radio and television stations will be completely, or almost entirely, crippled. It is beyond sad that some will die altogether.

In practical terms, that means people in smaller communities and rural areas who rely on their local public radio and television stations as their only sources of local news and information will be real victims of our nation’s already too large news deserts.

As NPR CEO Katherine Maher recently told media reporter Oliver Darcy’s Status newsletter, “Places without local news report higher rates of polarization, more distrust in their neighbors, lower trust in democratic institutions like voting, separation of powers, the civil service, the free press. They have lower rates of voter turnout, and fewer competitive elections.”

And that’s not to mention the fact that in many parts of our country, public TV and radio stations are their areas’ principal providers of emergency alerting, which means the National Weather Service and other agencies will have to find new ways to relay hurricane, tornado, flash flooding and additional types of warnings.

Is this really the outcome that those who oppose public broadcasting and outstanding responsible journalism desired?

When I was in St. Petersburg eight years ago, I’d go to the hotel restaurant for breakfast every morning. And every morning, on a loop, the TV in the restaurant would be showing “The Putin Interviews,” a four-part series for the US cable network Showtime in which film director Oliver Stone asked Putin one softball question after another. I would see it on televisions in electronics store windows. In Moscow one night, I took an Uber from a restaurant back to my hotel, and my interpreter remarked that the Stone-Putin interview audio was on the car radio. I couldn’t watch or hear anything else.

Is that the sort of thing that we want in the United States of America? No independent journalism; instead only state-run media running only what those currently in power want us to see and hear?

We may be headed in that direction. And I submit it is up to us, capital “J” journalists, to ensure otherwise. By asking the hard questions. By being tough but respectful to the subjects of our stories. By being completely transparent about how and why we report what we report. By promptly and prominently correcting any errors we may make.

By being journalists.