The future meets broadcast history at family-owned KSTP in the Twin Cities

By Kevin Finch,

Associate Professor, Former News Director

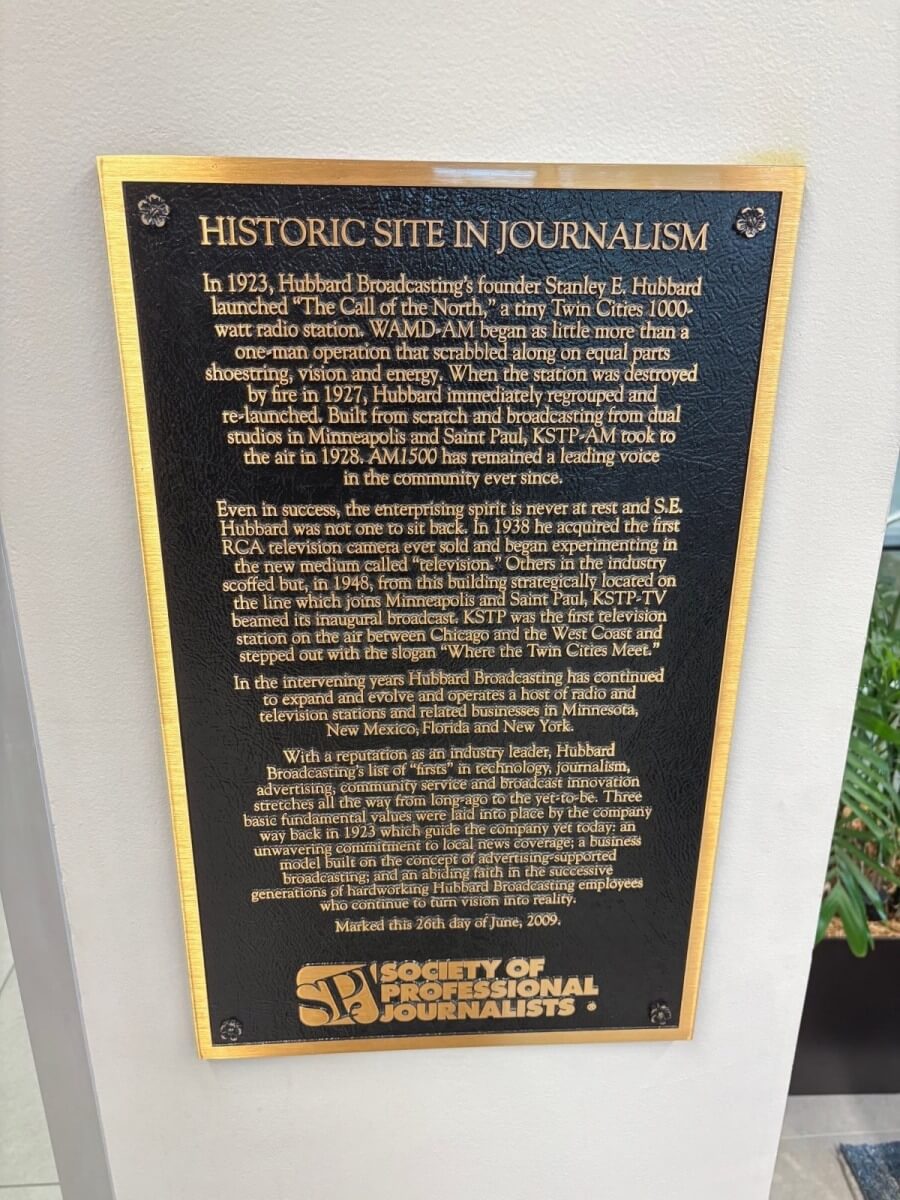

Daren Sukhram is a knowledgeable, energetic tour guide. There’s a lot to show off at KSTP in Minneapolis-St. Paul, a living monument to American broadcasting and journalism.

Sukhram, KSTP-TV’s assistant news director, points to the three legs of the tower on the property. One leg, he says, is in Minneapolis, the other in St. Paul and the third perches on the line between the two.

The idea of the precise location was founder Stanley E. Hubbard’s. The goal was to prove to both communities, especially their advertisers, that both of the Twin Cities would get their due with no favoritism. After all, the call letters mention only St. Paul.

Historic site in journalism. Cutline: All photos by the author.

Proof of the success of that move shows up in the sprawl of the building, which also houses a large cluster of radio stations, and in the signatures on the old concrete blocks near an entrance to a television studio. Actors, musicians, politicians, including Bob Hope and future Pres. Richard Nixon, left behind their autographs on the wall of the first television station between Chicago and the West Coast.

KSTP was a go-to for the famous and for the viewers who wanted to watch them.

Perhaps it’s appropriate that Minnesota station beat the FCC’s Television Freeze by going on the air in 1948, avoiding the agency’s four-year TV license hiatus while it sorted through all the applications and technical issues.

But it’s 2025 and Sukhram and his boss, News Director Michael Garber, know history won’t deliver today’s viewers, social media users and web readers.

For all the firsts at KSTP Channel 5, the one missing is first place across the board.

Garber summons a plethora of numbers to make his point.

“We are fourth in preference. We gotta do something. It’s not going to change in six months or a year.”

By the numbers

More numbers: Garber says morning news is often first or second overall according to Comscore, but third or fourth in key Nielsen demos.

“If we can get to second place at 5:00 (p.m.), we are closer to second at 5:00 than third at 10:00.”

In other words, KSTP is often third place at 5:00 p.m. and usually third or fourth at 10:00 p.m.. The 16th market is ultra-competitive. There’s another legacy station: CBS-owned WCCO, plus Tegna’s KARE, and Fox-owned KMSP.

Garber, who has been at the station since March, is direct but enthusiastic.

“It’s about being disciplined in what you do. Can you break away from what you’ve always done?”

Garber alternates between an analytical approach and sounding like a coach for the Vikings or Minnesota Wild.

“If we are just as good, there’s not a reason to watch. We can’t be just as good.”

He was speaking to this writer but clearly, he had his whole shop in mind. He uses coaches’ words such as “discipline” and “focus.”

“You’ve got to tear down some of the institutional stuff and make it viewer-centric.”

He shared that message at a meeting with his meteorologists while also noting improvements in late spring social media numbers.

Facebook views were up 54 percent in May, while interactions increased 126 percent.

Instagram weather viewing popped 457 percent, while interactions were double that.

But the meeting switched from encouraging numbers to the focus and discipline Garber evangelizes, as the meteorologists talked about the procedure for severe weather alerts.

One weather person lays out the forecast details in every morning and afternoon meeting, with digital and other representatives chiming in before the usual story pitches and logistical planning.

Much of the work takes place before those official gatherings in the “meeting before the meeting in Garber’s office.” Sukhram and the shift executive producer huddle with Garber to review available personnel for the day and to make sure they don’t miss the obvious stories, while they consider what will differentiate Channel 5 from the competition that day.

The dayside executive producer is Delaney Wright, a graduate of the state’s Big 10 school, the University of Minnesota.

The multi-purpose desk and producers

After the morning meeting, she coordinates with the Content Desk, a unit of eight journalists on different shifts who quietly handle the daily details that keep a newsroom on top of stories and immersed in digital story production.

“They monitor social, reach out and source video, get contacts. They write web copy, check court cases, even sit in on trials,” Wright said. They also handle the station’s streaming each day.

Eventually, Wright digs into the producers’ copy, looking for “new, now and next” writing and stressing the fundamentals.

But she is passionate about providing a work-life balance for the producers. Wright knows what it’s like to walk away from the newsroom.

“I took off news for a year,” because, she said, she had to answer the question, “Is this what I want to do with my life?”

After a year in non-profit communication, she came back because she “missed the newsroom and the people I worked with.”

A family affair

It’s cliché to say a company or office is like a family, but in the case of KSTP, it’s true. Several Hubbards are in key management positions today. They are Stanley E. Hubbard’s grandchildren, the company’s third generation in broadcasting and related fields. And the fourth generation is on the job at a couple of Hubbard stations.

U.S. map of stations Hubbard owns. Cutline: This map of the United States adorns the lobby of KSTP, showing Hubbard properties across the country.

The Hubbard family owns two smaller market Minnesota TV stations, as well as KSTP, plus stations in two upstate New York markets, one in New Mexico, the Reelz cable TV network, and a larger radio footprint including Washington, DC, South Florida, Phoenix, St. Louis, Cincinnati, and, of course, Minnesota.

Hubbard is not the only family group left, but in the past few decades, the Binghams, the Meyers, the Wolfes and others have sold their TV stations.

Graham, Capitol, Morgan Murphy, and Manship are among those who still have that family owner kinship with Hubbard.

TVNewsCheck ranks the company No. 15 among TV station groups (corporate and family), based on revenue. And Hubbard reinvests in its stations with automated production and other tech.

An early evening newscast live in KSTP’s automated TV production control room.

The Minneapolis market might end up with a Nexstar station if its proposed takeover of Tegna goes through. But unlike some other large markets, there are no multi-station/single ownership issues if the purchase takes place.

Al Tompkins at Poynter reminds us that the FCC would have to formally remove the 39 percent ownership cap. Beyond regulation, there is also the business of a buyout. Tompkins says Tegna may have another suitor, Sinclair, which might affect Nexstar’s plan to take over by the second half of 2026.

“But that plan still depends on Tegna shareholders, who may yet consider Sinclair’s competing offer,” Tompkins said in a Poynter piece published a week ago.

All that maneuvering with the FCC and corporate boardrooms would not appear to have much of a direct effect on KSTP. And in June, when this writer visited the station, that was not top of mind.

Multi-platforms in practice

Covering local news for multiple platforms was. That included a bizarre domestic violence situation in the suburb of Brooklyn Center, in which a suspect emerged from a home wielding a chainsaw.

Coverage continued into the next morning with reporter Bailey Hurley and photographer Nick Gaither doing live shots all the way into the midday news.

KSTP photographer Nick Gaither shoots a live standup by reporter Bailey Hurley in Brooklyn Center, Minn., on June 12.

The Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension later identified five police officers who used regular firearms and non-lethal force on the suspect, who survived. But those details were not available when KSTP reporter and weekend anchor Brett Hoffland and photographer Jared Bergerson arrived on the scene.

They still had to provide an update on the nervous neighborhood, where there were still police cars present and few answers about how the situation escalated.

Jared Bergerson films an active standup for TV with reporter Brett Hoffland.

Hoffland and Bergerson had to feed … the beasts. Not just television, but the new industry standard vertical video for use on the station’s social media platforms.

Brett Hoffland lives the multi-platform life, shooting a vertical video standup, explaining the status of a Brooklyn Center, Minn. neighborhood the day after an unusual case of alleged domestic violence.

Hoffland made the most of his time waiting for a police update as he balanced two laptops in his car.

“I’m just going through what the (already) photographer shot,” he said. Hoffland expected to get new sound from neighbors (many were not home in the middle of the day) and police.

Hoffland reviews video and stays in touch with the station until he can do more interviews at the crime scene.

The important thing here is that he did not need to drive south back to the station. He could communicate with producers, write and view video, all from the same front seat.

That’s hardly new tech or a new idea, but it is a best practice that is still too inconsistently applied in many shops.

News director Michael Garber would be pleased with that effort and with the vertical video.

“We’re becoming better at that.”

“Everyone (on staff) deserves growth because they work hard.” Garber added, “It’s good for the family, too.”

A few conclusions from the writer

My goal was to visit two stations in two time zones, north and south, one corporate and the other family owned. The idea was to observe TV newsrooms during regular operations, not Super Bowl week or election night or the Olympics.

Bob Papper’s 2025 Syracuse University report for RTDNA revealed a trend that I saw in action: Larger stations are not emphasizing the use of MMJs (or MSJs) as they were in the previous decade.

But both stations have jumped on vertical videos to communicate with viewers in their natural habitat—smart phones held with one hand. It is the way viewers watch video on their phones, despite early efforts to get them to turn the phone horizontally to mimic TV aspect ratio.

Stations are also streaming much more video and recognizing that each platform—social, YouTube, streaming, broadcast, and websites—represent different viewer expectations.

A viewer may welcome a fully produced news program via streaming but that may not work on YouTube, for instance.

Delivery systems aside, it still comes down to what newsrooms place on those platforms. Local stories, reliable weather coverage, and enterprise and investigative pieces that differentiate one newsroom from the next are the fuel for those different delivery systems.

I also observed attention to detail in everything from copy editing to production quality. Both stations provided me with plenty of best practices to share with my students.

Finally, full disclosure: I knew people at both stations. But if you have a lengthy career in TV news, that’s hard to avoid.